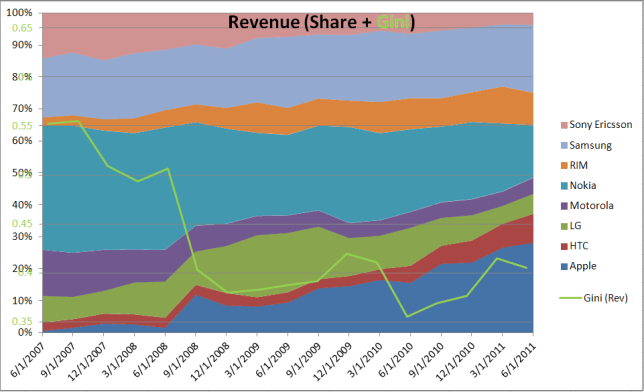

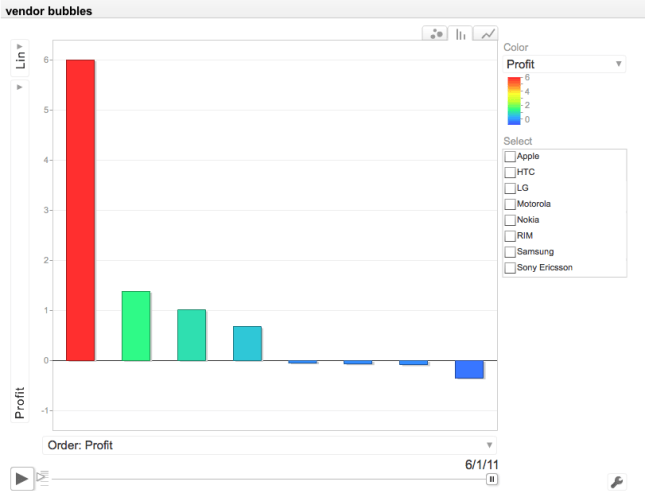

In a previous post we looked at inequality of profits and the useful abstraction of the Whale-Curve to analyze Customer Profitability. Here I want to focus on inequality and its measurement and visualization in a broader sense.

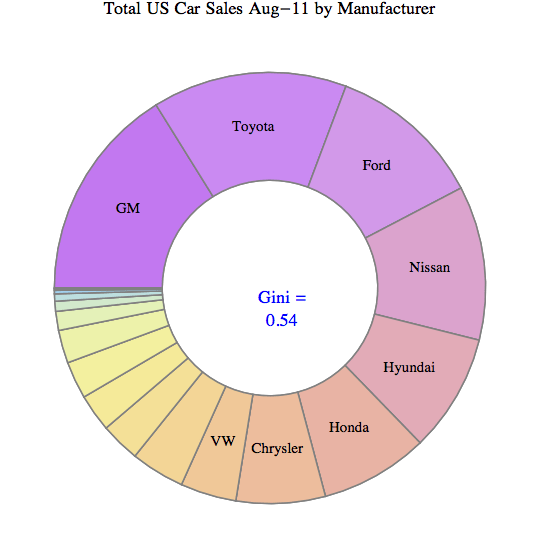

A fundamental graphical representation of the form of a distribution is given by the Lorenz-Curve. It plots the cumulative contribution to a quantity over a contributing population. It is often used in economics to depict the inequality of wealth or income distribution in a population.

Lorenz Curve (Source: Wikipedia)

The Lorenz-Curve shows the y% contribution of the bottom x% of the population. The x-axis has the population sorted by increasing contributions; (i.e. the poorest on the left and the richest on the right). Hence the Lorenz-Curve is always at or below the diagonal line, which represents perfect equality. (By contrast, the x-axis of the Whale-Curve sorts by decreasing profit contributions.)

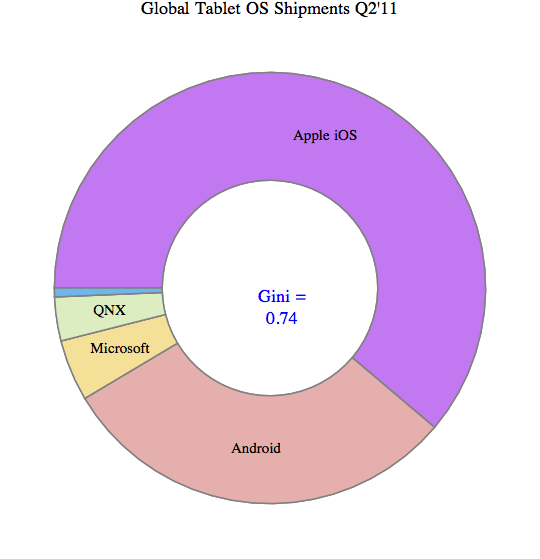

The Gini-Index is defined as G = A / (A + B) , G = 2A or G = 1 – 2B

Since each axis is normalized to 100%, A + B = 1/2 and all of the above are equivalent. Perfect equality means G = 0. Maximum inequality G = 1 is achieved if one member of the population contributes everything and everybody else contributes nothing.

An interesting interactive graph demonstrating Lorenz-Curves and corresponding Gini-Index values can be found here at the Wolfram Demonstration project.

The GINI Index is often used to indicate the income or wealth inequality of countries. The corresponding values of the GINI index are typically between 0.25 and 0.35 for modern, developed countries and higher in developing countries such as 0.45 – 0.55 in Latin America and up to 0.70 in some African countries with extreme income inequality.

GINI index of world countries in 2009 (Source: Wikipedia)

Graphically, many different shapes of the Lorenz-Curve can lead to the same areas A and B, and hence many different distributions of inequality can lead to the same GINI index. How can one determine the GINI index? If one has all the data, one can numerically determine the value from all the differences for each member of the population. An example of that is shown here to determine the inequality of market share for 10 trucking companies.

Another approach is to model the actual distribution using a formal statistical distribution with known properties such as Pareto, Log-Normal or Weibull. With a given formal distribution one can often calculate the GINI index analytically. See for example the paper by Michel Lubrano on “The Econometrics of Inequality and Poverty“. In another example, Eric Kemp-Benedict shows in this paper on “Income Distribution and Poverty” how well various statistical distributions match the actually measured data. It is commonly held that at the high end of the income the Pareto distribution is a good model (with its inherent Power law characteristic), while overall the Log-Normal is the best approximation.

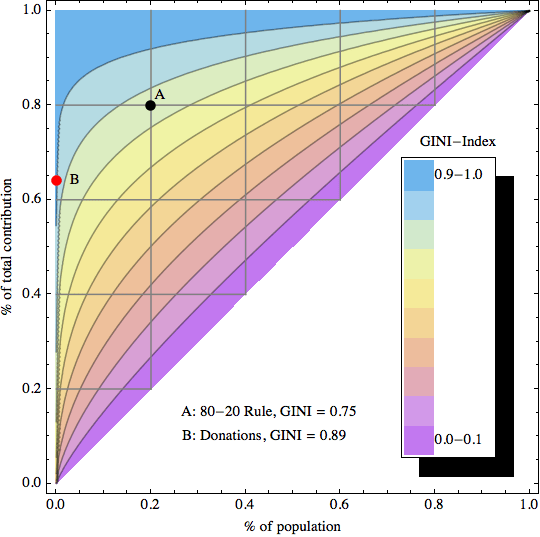

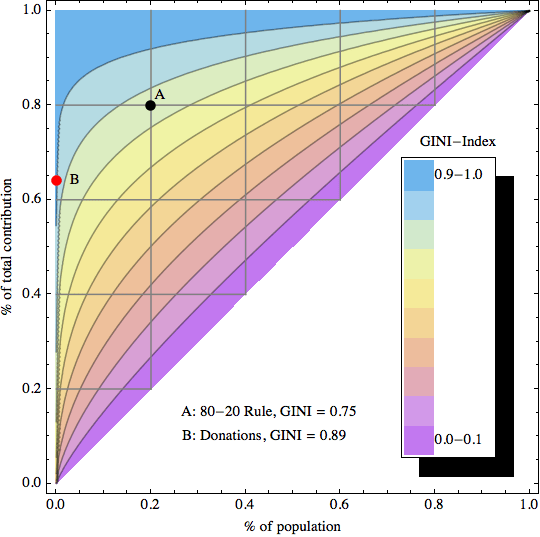

After studying several of these papers I started to ask myself: If x% of the population contribute y% to the total, what’s the corresponding GINI index? For example, for the famous “80-20 rule” with 20% of the population contributing 80% of the result, what’s the GINI index for the 80-20 rule?

To answer this question I created a simple model of inequality based on a Pareto distribution. Its shape parameter controls the curvature of the distribution, which in turn determines the GINI index. The latter is visualized as color-coded bands using a 2D contour plot in the following graphic:

GINI index contour plot based on Pareto distribution model

The sample data point “A” corresponds to the 80-20 rule, which leads to a GINI index of about 0.75 (strongly unequal distribution). Data point “B” is an example of an extremely unequal distribution, namely US political donations (data from 2010 according to a statistic from the Center of Responsive Politics recently cited by CNNMoney):

“…a relatively small number of Americans do wield an outsized influence when it comes to political donations. Only 0.04% of Americans give in excess of $200 to candidates, parties or political action committees — and those donations account for 64.8% of all contributions”

0.04% contribute 64.8% of the total! Here is another way of describing this: If you had 2500 donors, the top donor gives twice as much as the other 2499 combined. This extreme amount of inequality corresponds to a GINI index of 0.89 (needless to say that this does not seem like a very democratic process…)

As for US income I created a separate graphic with data points from the high end of the income spectrum (where the underlying Pareto distribution model is a good fit): The top 1% (who earn 18% of all income), top 0.1% (8%), and top 0.01% (3.5%).

GINI Index Contour Plot with high end US Income distribution data points

These 3 data points are taken from Timothy Noah’s “The United States of Inequality“, a 10-part article series on Slate, which in turn is based on data and research from 2008 by Emmanuel Saez and visualizations by Catherine Mulbrandon of VisualizingEconomics.com. This shows the 2008 US income inequality has a GINI Index of approximately 0.46, which is unusually high for a developed country. Income inequality has grown in the US since around 1970, and the above article series analyzes potential factors contributing to that – but that’s a topic for another post. In the spirit of visualizing data to create insight, I’ll just leave you with this link to the corresponding 10-part visual guide to inequality:

Postscript: In April 2012 I came across a nice interactive visualization on the DataBlick website created by Anya A’Hearn using Tableau. It shows the trends of US income inequality over the last 90 years with 7 different categories (Top x% shares) and makes a good showcase for the illustrative power of interactive graphics.